This article is the record of an ongoing collaboration with one of Canada’s finest knife makers to reproduce to the best of his ability with limited primary sources what Horace Kephart promoted as his ideal knife, one he had commissioned from a local blacksmith he knew. The nuances of his knife could only be made by a skilled smith, even today modern machinery are unable to reproduce all the details of what makes Kephart’s knife so special.

Some information about the craftsman who is behind the knives:

Darcy Quapp was born in southern Alberta Canada in 1967. He started making knives in high school in the 1980’s, and according to his own words got fairly serious in 1987. After watching last of the Mohicans he started making forged frontier knives for a few years, then life got busy and he got married and had seven kids. He never completely stopped making the odd knife here and there. About 5 years ago Mr. Quapp started making axes and then pipe tomahawks, his interest in making early style North American knives was rekindled. His edged blade business has grown along with his thriving metal fabricating business. He is a professional welder fabricator and makes all of his own tools for his shop, he even made his shop power hammer and press. With his incredible experience and portfolio I am honored to have teamed up with him to make the historical knives that will be featured in an upcoming YouTube series where we will use and compare the two knives from two of history’s prolific outdoorsmen, Nessmuk and Horace Kephart, out in the field under typical and historical woodcraft tasks. The best way to contact Mr. Quapp about commissions is through his Facebook page Prairie Forge and Axe and contact him via messenger. Let him know Mr. Dyer sent ya!

The Birth of the Kephart knife:

A Brief History of Horace Kephart

Horace Kephart was born on September 8, 1862 in East Salem Pennsylvania and lived until April 2, 1931, he died in a car accident and is buried near Bryson City North Carolina. Mr. Kephart is most well known for his contributions to outdoor recreation, the most lasting being his book Camping and Woodcraft published in 1906. You can find his book and more by clicking My Suggested Booklist at the top of the page or clicking HERE. He contributed articles to many magazines and journals of his time, he was a trained librarian and a prolific writer, you can find an incredible bibliography of all his writings HERE. In 1886 he accepted a prestigious position as the librarian at Yale University in Connecticut. In 1890 Kephart accepted a position as the director of the St. Louis Mercantile Library Association, in this position he built the largest collection of Western Americana of the time to include diaries, newspapers, letters, manuscripts, court records, and anything else that could be considered historically important to the social and political history of the west.

His life consisted of a tremendous amount of time spent in pursuing the outdoors. Even though he was married, as time went on his attentions were directed to an outdoor and wilderness lifestyle, in 1904 he resigned his position after his doctor suggested he leave professional life after suffering from a nervous breakdown. He abandoned his wife and six children to live in Hazel Creek North Carolina where he wrote Camping and Woodcraft: A Guidebook for Those Who Travel in the Wilderness. Even today the wisdom in that book is valuable for the outdoor recreation enthusiast. To pay his bills he wrote for magazines and journals specializing in outdoor recreation and also authored several books. Ever the academic, he wrote a history and commentary of southern Appalachian life titled Our Sothern Highlanders. The following passages comes from the 1909 edition of Kephart’s The book of camping and woodcraft; a guidebook for those who travel.

“On the subject of hunting knives I am tempted to be diffuse. In my green and callow days (perhaps not yet over) I tried nearly everything in„ . the knife line from a shoemaker’s skiver to a machete, and I had knives made to order. The conventional hunting knife is, or was until quite recently, of the familiar dime-novel pattern invented by Colonel Bowie. Such a knife is too thick and clumsy to whittle with, much too thick for a good skinning knife, and too sharply pointed to cook and eat with. It is always tempered too hard. When put to the rough service for which it is supposed to be intended, as in cutting through the ossified false ribs of an old buck, it is an even bet that out will come a nick as big as a saw-tooth—and Sheridan forty miles from a grindstone! Such a knife is shaped expressly for stabbing, which is about the very last thing that a woodsman ever has occasion to do, our lamented grandmothers to the contrary notwithstanding.

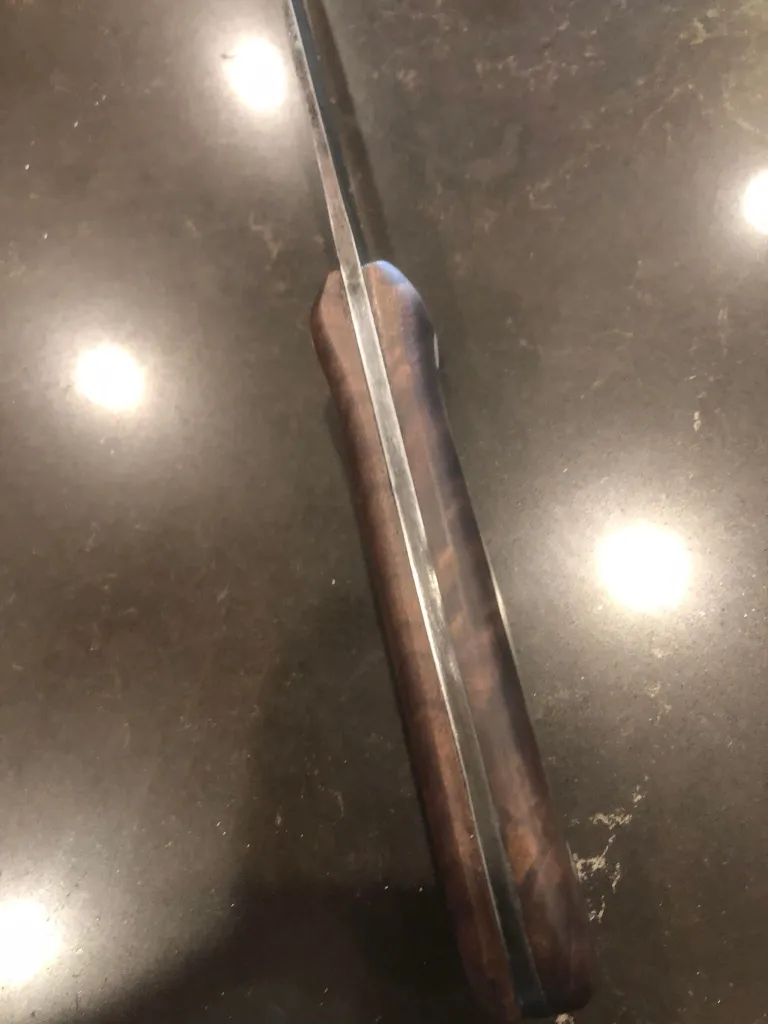

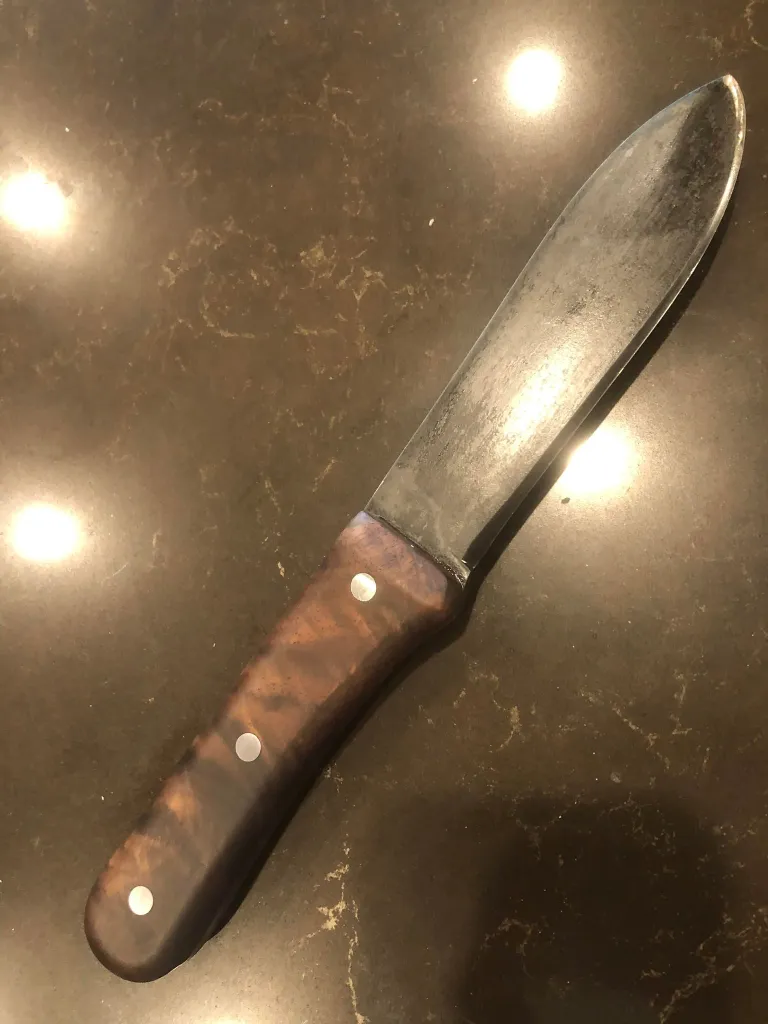

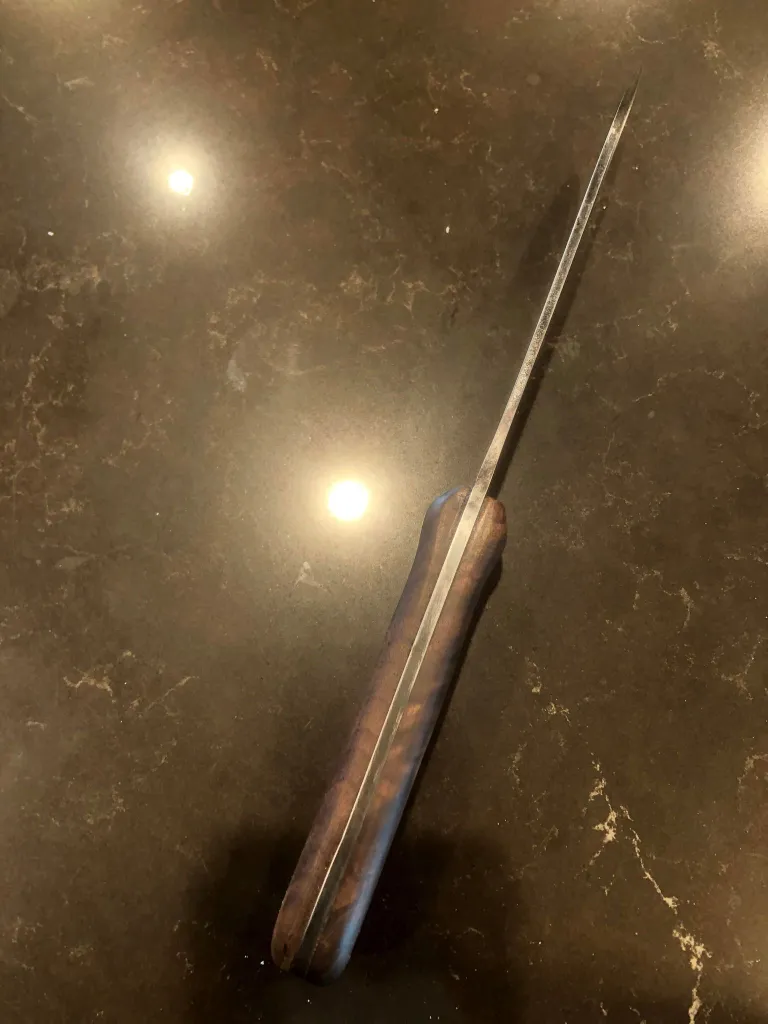

A camper has use for a common-sense sheath-knife, sometimes for dressing big game, but oftener for such homely work as cutting sticks, slicing bacon, and frying “spuds.” For such purposes a rather thin, broad pointed blade is required, and it need not be over four or five inches long. Nothing is gained by a longer blade, and it would be in one’s way every time he sat down. Such a knife, bearing the marks of hard usage, lies before me. Its blade and handle are each 4 inches long, the blade being 1 inch wide, 1 1/8 inch thick on the back, broad pointed, and continued through the handle as a hasp and riveted to it. It is tempered hard enough to cut green hardwood sticks, but soft enough so that when it strikes a knot or bone it will, if anything, turn rather than nick; then a whet stone soon puts it in order. The Abyssinians have a saying, “If a sword bends, we can straighten it; but if it breaks, who can mend it ?” So with a knife or hatchet.

The handle of this knife is of oval cross-section, long enough to give a good grip for the whole hand, and with no sharp edges to blister one’s hand. It has a 1/2 inch knob behind the cutting edge as a guard, but there is no guard on the back, for it would be useless and in the way. The handle is of light but hard wood, 3/4 inch thick at the butt and tapering to 1/2 inch forward, so as to enter the sheath easily and grip it tightly. If it were heavy it would make the knife drop out when I stooped over. The sheath has a slit frog binding tightly on the belt, and keeping the knife well up on my side. This knife weighs only 4 ounces. It was made by a country blacksmith, and is one of the homeliest things I ever saw; but it has outlived in my affections the score of other knives that I have used in competition with it, and has done more work than all of them put together. The Marble’s “expert” knife is a good pattern.” (1909, 28)